Assuming that the sponsor has passed your review [1] and the property meets your investment criteria [2,3], you have reached the final steps in your due diligence journey.

The opportunity looks promising. The sponsor may be encouraging you to commit quickly. You may feel excitement about the projected returns. This is precisely when you must set aside that excitement and focus on the numbers.

No matter how impressive the sponsor’s track record or how attractive the property appears, the deal itself can undermine your investment through unrealistic assumptions, misaligned incentives, or structural flaws. Your task is not to talk yourself into the deal, but to verify that the projections and structure support the promised outcome.

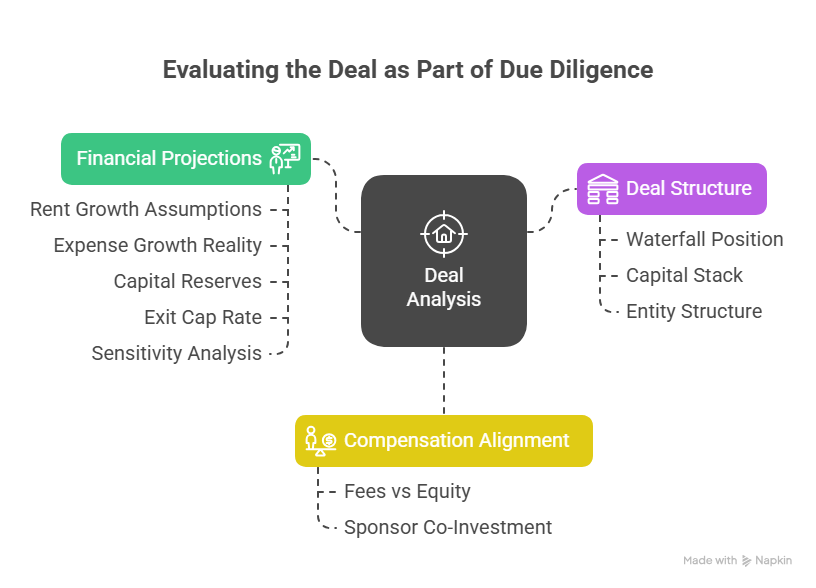

Three core areas require thorough understanding before you commit capital.

Understanding the Financial Projections and Their Assumptions

The pro forma shows what the sponsor expects to happen with income, expenses, and property value. Your job is to evaluate whether those expectations rest on solid ground or are wishful thinking.

Rent Growth Assumptions

Most pro formas project that rents increase over time, which is reasonable as rents generally trend upward with inflation. However, sponsors often use favorable rent growth assumptions to inflate projected returns.

Once the property reaches stabilization, projected rent growth should align with historical trends for that market. Review average annual rent increases over the past five to ten years in that neighborhood, and verify that the sponsor’s assumptions fall at or below that historical average. Even small differences matter. A deal projecting four percent annual rent growth instead of three percent will show dramatically higher returns over a seven-year hold, but if the market historically supports only three percent, your actual returns will likely be much lower than projections.

Ask the sponsor directly: “What is your assumed annual rent growth after stabilization, and how does that compare to the historical average for this submarket over the past decade?”

Expense Growth Reality

Income and expenses in a stabilized property should increase at roughly similar rates, as both face the same inflationary pressures.

A significant red flag appears when rents increase faster than expenses year after year. This pattern rarely occurs in stabilized commercial properties. Certain expenses like insurance and property taxes often increase faster than rents, compressing net operating income unless active management creates offsetting efficiencies.

For proper planning, you should expect to see expenses increasing at least as fast as projected rents. Strong sponsors will even model certain categories separately, showing insurance increasing at historical rates specific to that expense rather than applying a blanket inflation assumption across all costs.

If you see a deal where rents grow at four percent annually but expenses grow at only two percent, ask the sponsor why. The sponsor should be able to articulate specific operational improvements that will create those efficiencies. Without that justification, the projections are likely overly optimistic.

Capital Reserves and Contingency Planning

The pro forma should clearly identify reserves being accumulated throughout the hold period, building on reserves from the initial purchase of the property. Properties require ongoing capital expenditures regardless of inspection thoroughness.

Adequate reserves are essential protection. Yet many sponsors minimize reserve allocations because reserves reduce distributable cash flow and lower projected returns.

This short-sighted approach should concern you. Without sufficient reserves, a minor issue can escalate into a crisis. A property lacking cash to immediately address major plumbing failure or fire safety violations can deteriorate, lose tenants, and spiral downward.

The appropriate reserve amount varies based on property type, age, and condition. Rather than looking for a specific dollar amount, evaluate whether the sponsor has thoughtfully considered property-specific risks and allocated reserves accordingly.

Ask the sponsor: “How did you determine the appropriate reserve levels for this property, and what types of events are you planning to cover with those reserves versus pay out of the operating budget?”

The Exit Cap Rate Assumption

One of the most consequential assumptions is the exit cap rate [4], which determines projected sale price. This single assumption can make or break projected returns.

Cap rates represent the relationship between a property’s net operating income and its value. When sponsors assume they will sell at a lower cap rate than purchase, they are projecting premium valuation at exit compared to today. While this can happen, it is far from guaranteed and should not be a foundation for expected returns.

Best practice calls for sponsors to assume an exit cap rate slightly higher than entry, reflecting that properties age and markets change. However, given recent cap rate increases, having equal entry and exit cap rates is not unreasonable.

What should concern you is any deal assuming exit cap rate meaningfully lower than entry. Such projection counts on market appreciation, not operational improvement, to deliver returns.

When you see this pattern, probe deeply. Ask the sponsor: “Why do you believe the exit cap rate will be lower than today’s rate, and what happens to investor returns if we exit at the same cap rate we entered at?”

Sensitivity Analysis: Testing the Assumptions

A well-prepared sponsor should provide sensitivity analysis showing how changes in key assumptions such as cap rates, rent increases, expense increases, and loan interest rates affect returns. This reveals how fragile or resilient the deal is.

The analysis should demonstrate acceptable returns even when assumptions prove less favorable than projected. You want returns that degrade gradually if conditions worsen, not a deal requiring everything to go exactly as planned.

If the sponsor does not provide sensitivity analysis, that absence is itself a red flag suggesting they have not stress-tested their assumptions. In that case, be prepared to build a simple spreadsheet yourself. You do not need sophisticated modeling skills, just the ability to adjust key assumptions and observe how returns change.

Ask yourself: If rent growth is one percentage point lower than projected, if expenses grow one point faster, and if the exit cap rate equals the entry cap rate, does this deal still meet my investment criteria? If the answer is no, the deal may be too dependent on optimistic assumptions.

Operational Assumptions and Property-Specific Plans

Beyond financial projections, you must understand the sponsor’s operational plan and evaluate whether it is realistic given the property’s location and condition.

If the sponsor is pursuing value-add strategy with renovations or amenities, verify that projected rent increases are achievable. Adding a pickleball court will not dramatically transform rents. Even comprehensive renovations cannot overcome fundamentally undesirable location.

The most reliable evaluation method is examining comparable properties in the immediate area that already feature the planned improvements. What rents do those properties achieve? After adjusting for unit size, age, and location differences, do the sponsor’s projections align with comparable data?

If projections exceed what similar properties currently command, the sponsor assumes they will outperform the market. That may be possible, but requires explanation.

Neighborhood Dynamics and the Line of Progress

Understanding the specific neighborhood is critical. Neighborhoods within the same city differ dramatically in crime, schools, employment, and demographics. These factors impact both execution difficulty and rent growth likelihood.

Some sponsors pursue “line of progress” strategy, acquiring properties at the edge of less desirable neighborhoods to improve the property and help shift boundaries. When successful, this produces exceptional returns from both property and neighborhood improvement.

However, this carries substantial risk. The line can move in either direction, potentially leaving you deeper in declining areas.

If the sponsor pursues this strategy, verify their track record with similar projects. Examine trends supporting their plan: new commercial investment from national retailers, young professionals moving in, or declining crime. Negative indicators include rising vacancy, store closures, or demographic shifts away from the area.

The sponsor should articulate specific evidence supporting their neighborhood thesis, not just general optimism.

Evaluating the Deal Structure and Capital Stack

Understanding how the deal is structured determines not just how you get paid, but whether you get paid if things do not go as planned. Structure defines your position in the hierarchy of claims on cash flow and your risk exposure.

Your Position in the Waterfall

You should already understand investor share classes, preferred returns, and waterfall structures [5]. The critical question now is: Where do you sit in the payment hierarchy?

In deals with multiple investor classes, certain shareholders may receive distributions, sometimes in full, before others receive anything. If the deal underperforms, losses are not equal. Some investors may receive their preferred return while others receive nothing.

This structure is neither inherently good nor bad, but you must understand your position clearly. If you are in a junior class receiving distributions only after senior classes are paid, you need compensation for that additional risk through higher potential returns. Without awareness of your junior position, you take risk you never agreed to accept.

Ask the sponsor: “Please explain each share class in this deal, the payment priority between them, and specifically where my investment falls in that hierarchy.”

The Complete Capital Stack

Beyond equity investor classes, you must understand every capital stack layer because each has a claim on cash flow ahead of yours as an equity investor.

Nearly every deal includes debt, meaning a lender must be repaid in full before you receive capital back. However, the stack often extends beyond a single loan. Many deals include senior debt, mezzanine debt (second or third position loans), and preferred equity holders who all must be paid before general equity investors receive distributions.

These capital providers typically set terms the sponsor must meet before making distributions: mandatory reserves, minimum debt service coverage ratios, or capital expenditure restrictions. Some stakeholders may have the ability to take control or force a sale if terms are not met, even if that action does not serve your best interest.

For example, preferred equity has entered many deals in recent years specifically to prevent foreclosure. These preferred equity investors often negotiated significant control rights and high return thresholds that effectively subordinate original equity investors.

The capital stack may evolve over the deal’s life as sponsors navigate changing conditions, but you should understand the intended structure from the beginning. This allows you to assess the likelihood of receiving distributions and how much cushion exists between projected performance and the point where you get cut off from cash flow.

A deal with heavy debt load, mezzanine financing, and preferred equity may look attractive on paper but leaves minimal room for error before equity investors are effectively wiped out.

Understanding the Entity Structure

Most syndications involve at least three separate legal entities, each serving a distinct role. Understanding their relationships is essential for evaluating risk.

First is the entity holding title to the property. In many deals, this is the entity you purchase shares in directly. However, in fund structures, additional entity layers may exist between you and the actual property owner. Understanding where your ownership fits determines your legal rights and protections.

Second is the managing entity. While you may think of the sponsor as a person, the manager is typically a legal entity owned by the sponsor and any co-sponsors. The manager should make strategic decisions about the property. Within the managing entity, you should identify the specific individual or group responsible for key decisions.

Beyond that, you must understand the succession plan for the manager. Key person risk is real in partnerships that may last a decade. If the primary decision maker becomes incapacitated or dies, who takes over? Many smaller operators fail to create succession plans, leaving investors unnecessarily exposed.

Third is the property operator. Understanding their relationship to both manager and property-owning entity reveals important risk factors [6]. Are they independent contractors who can be replaced if they underperform? Are they actually the property owners who are contracting out management to your entity? Are they co-investors alongside the manager?

Their decision-making authority, contractual relationships, and financial stake all impact your risk profile.

In more complex transactions, many additional entities may be involved. As a general rule, more entities mean more complexity and often more risk. While certain structures like fund-of-funds may reduce risk through diversification, many multi-entity structures create additional failure points without effectively mitigating risk.

For each entity in the deal, understand its role, its relationship to other entities, and how it is compensated.

Analyzing Compensation and Incentive Alignment

How each entity and individual gets paid reveals whether their incentives align with yours. Misaligned incentives create situations where sponsors or operators profit even when you lose money.

Fees Versus Equity Participation

Many entities supporting a syndication are compensated through fees rather than equity participation in the deal’s success. Developers, property managers, and construction managers commonly receive fees for services. If an entity receives only fee-based compensation, they profit even when the deal fails to meet projections.

This is not inherently problematic. Service providers need adequate compensation to perform their roles. You do not want a property manager cutting maintenance corners because they are underpaid. However, you want the majority of compensation for key decision makers to come from the deal’s success, not from fees collected along the way.

Ideally, the sponsor’s largest payday occurs when the property sells and equity investors receive projected returns. This ensures the sponsor remains focused on maximizing ultimate outcome rather than simply collecting fees.

Review the fee structure carefully. Acquisition fees, asset management fees, property management fees, refinancing fees, and disposition fees can accumulate substantially. While each individual fee may seem reasonable, together they can significantly drag on returns.

Ask the sponsor: “Please itemize all fees that you or related entities will receive throughout the life of this investment, and explain how those fees relate to the equity-based compensation you will receive at exit.”

The Question of Sponsor Co-Investment

Many investors look for sponsors to have “skin in the game” through capital investment alongside limited partners. The theory is that sponsors risking their own money will be more motivated toward success.

While sponsor co-investment is generally desirable, it is not as reliable an indicator as commonly believed, and should not be your primary evaluation criterion.

First, sponsors can convert acquisition fees or other compensation into equity shares rather than taking cash. This costs them nothing out of pocket and can make their investment appear larger than it is. If the deal fails, they have not truly lost anything because they never contributed cash.

Second, you want sponsors to maintain sufficient liquidity to support deals when unexpected issues arise. A sponsor who can make an interest-free loan to cover short-term cash flow problems or contribute capital for unexpected major repairs adds significant value. If all the sponsor’s capital is tied up in existing investments, they lack that flexibility.

Bringing It All Together: Disciplined Evaluation in the Face of Opportunity

You have now reviewed three comprehensive areas: the financial projections and assumptions, the structural hierarchy of the deal, and the compensation arrangements for all parties. This is demanding work that requires focused attention and the discipline to ask uncomfortable questions.

This is also the point where many investors falter. The deal looks promising. The sponsor has a track record. Other investors are committing. The pressure to move forward intensifies, both from external sources and from your own excitement about the opportunity.

Remember why you began this due diligence process. You are not searching for reasons to invest. You are searching for evidence that this specific deal, with this specific sponsor, using these specific assumptions, and structured in this particular way, will reliably produce the returns you need to meet your financial goals. That evidence must be concrete, verifiable, and grounded in realistic assumptions about the future.

Your job is not to believe in the deal. Your job is to evaluate whether the deal can deliver even when conditions prove less favorable than the sponsor projects.

The most successful investors are not the ones who find the most deals to invest in. They are the ones who say no to opportunities that do not meet their standards, even when those opportunities look attractive on the surface. They are the ones who walk away from deals with sponsors they like when the numbers do not support the projections. They are the ones who keep their emotions in check and focus relentlessly on what the data actually shows.

Before you commit your capital, return to the core questions this article has equipped you to answer:

On Financial Projections:

- Do the rent growth assumptions align with historical averages for this specific market?

- Are expenses projected to grow at least as fast as income?

- Are reserves adequate for the property type and condition?

- What happens to my returns if the exit cap rate equals or exceeds the entry cap rate?

- Has the sponsor provided sensitivity analysis, and does the deal still work under less favorable scenarios?

On Deal Structure:

- Where exactly do I sit in the payment waterfall?

- What layers of debt and preferred equity must be paid before I receive distributions?

- Do I understand the role of each entity involved and their relationships to each other?

- Is there a succession plan if the key decision maker becomes incapacitated?

On Compensation and Alignment:

- How much of the sponsor’s compensation comes from fees versus equity participation?

- Is the fee structure reasonable relative to the services being provided?

- Will the sponsor’s largest payday come when I receive my projected returns?

If you cannot answer these questions with confidence, you should not invest. Go back to the sponsor and request the information you need. A high-quality sponsor will welcome your diligence and provide clear, thorough answers. A sponsor who becomes defensive, evasive, or pressures you to commit before you have completed your analysis is revealing something important about how they will behave throughout the partnership.

Performing thorough due diligence on the sponsor, the property, and the deal requires significant time and effort. However, this investment of your time and attention now prevents far larger losses later. Failing to complete this work will almost certainly result in investments that do not meet your expectations.

The discipline you demonstrate at this stage, the willingness to ask difficult questions and to walk away from deals that do not meet your standards, is what separates successful passive investors from those who chase returns and end up with disappointing results.

Remember, your goal is not to become an expert real estate analyst. Your goal is to become a discerning investor who can recognize when a deal is built on solid foundations and when it rests on optimistic assumptions and misaligned incentives. This article and the preceding ones have given you the framework to make that distinction. The discipline to apply that framework consistently is up to you yours to maintain.

For additional reading:

- https://www.mbc-rei.com/blog/72-vetting-a-syndication-sponsor/

- https://www.mbc-rei.com/blog/61-establishing-your-investment-thesis-part-1-define-your-goal/

- https://www.mbc-rei.com/blog/76-beyond-the-sponsor-analyzing-the-property-that-will-generate-your-passive-income/

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/capitalizationrate.asp

- https://www.mbc-rei.com/blog/what-is-a-preferred-return-and-how-does-it-relate-to-a-waterfall/

- https://www.mbc-rei.com/blog/65-understanding-gp-operator-relationships-critical-due-diligence/

The complete set of newsletter archives are available at:

https://www.mbc-rei.com/mbc-thoughts-on-passive-investing/

This article is my opinion only, it is not legal, tax, or financial advice. Always do your own research and due diligence. Always consult your lawyer for legal advice, CPA for tax advice, and financial advisor for financial advice.